Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome by Art History Professor Penelope Davies has been published by Cambridge University Press. It is the first book to explore the intersection between Roman Republican building practices and politics (c.509-44 BCE).

At the start of the period, architectural commissions were carefully controlled by the political system; by the end, buildings were so widely exploited and so rhetorically powerful that Cassius Dio cited abuse of visual culture among the reasons that propelled Julius Caesar's colleagues to murder him in order to safeguard the Republic. Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome covers the early Republic, the plebeians' struggle for equality, the years of Mediterranean expansion, and the gradual unraveling of senatorial control. In its closing chapters, Davies examines the dictatorship of Caesar, the first Republican to propose large-scale city planning. In the book’s introduction, Davies writes:

It was in a city’s interest to have grand public buildings and spaces, not only for its own functioning but also to vie with other states for prestige. Construction was perceived as the responsibility and the hallmark of local ruling elites, usually monarchs; architecture gave them visibility and helped to legitimize their status, and did so in at least two ways: first, through acts of benefaction, their initiatives improved standards of living for their subjects; and second, by masterminding space, they framed the daily ceremonies of life and the rituals of elite power. In Rome, though, things worked differently. For an elite that strove constantly to negotiate status with the voting public, visibility enhanced electability and augmented prestige, which made it all but irresistible for even the most committed Republican to use buildings as a tool for self-advancement.

In an engaging and wide-ranging text, Davies traces the journey between two points, as politicians developed strategies to maneuver within the system's constraints.

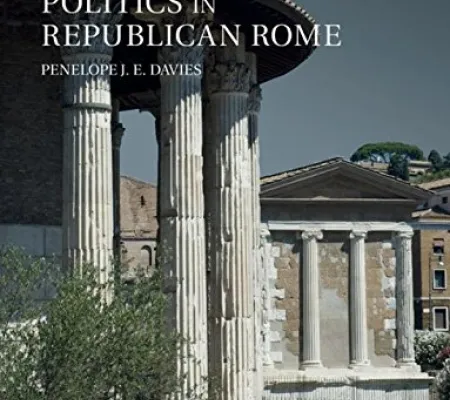

Davies also explores the urban development and image of Rome, setting out formal aspects of different types of architecture and technological advances such as the mastery of concrete. Elucidating a rich corpus of buildings that have been poorly understood, Davies demonstrates that Republican architecture was much more than a formal precursor to that of imperial Rome.

“In this perceptive book, Davies interrogates the evolving, mutually exploitative exchange between architecture and politics in Rome of the Republic,” writes Diane Favro in advance praise of Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome. “Drawing on deep research, she expertly reveals how such factors as term limits, religious traditions, materials, and cultural shifts constrained and enriched politicians and architectural projects alike. It is an informative and compelling story, told with verve and insight.”